‘I want no misunderstanding. We will not shirk our duty. We are not withdrawing. We are staying here.’

Unfortunately for many Afghans, this quote by an American secretary of state is 75 years old. It stems from a speech given in Stuttgart, on 6 September 1946, which is hardly remembered, but definitely worth remembering as a milestone in what turned out to be the most successful attempt ever in nation-building by occupation, democratic re-education, and economic support. The nation thus built is currently – in an eerie coincidence with the American withdrawal from Afghanistan – ‘snoozing toward its federal election’, enjoying a campaign led by ‘boring’ candidates, and in which ‘a premium is put on being dull’. Boring – an adjective that is, when applied to nation-states and their political systems, probably the ultimate blessing.

A post-war tipping point

In 1946 Germany was, alas, anything but boring. The humanitarian situation was more than dire in every respect and source of much concern, especially within the American administration. And the fault lines in the so-called ‘Allied Control Council’, already visible at the 1945 Potsdam Conference, were deepening – mainly due to the thorny issues of reparations, the uncertainty around the future of the Ruhr, and the increasing difficulty of finding a solution (= peace treaty) that would avoid a permanent territorial division of the country (and by consequence the formation of two or more different states). There were also quite contradictory viewpoints within American diplomacy.

Hope in times of great uncertainty

James F. Byrnes, who was Secretary of State for only roughly eighteen months between mid-1945 and January 1947, was a rather ambiguous character. Involved in the Manhattan Project, he did not have any second thoughts about dropping the atom bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. And he was a keen supporter of segregationist education in his time as governor of South Carolina. Byrnes is not half as well-known as his successor, George Marshall, but parts of the ‘Speech of Hope’ sound like a first draft for the famous Harvard speech ten months later. True, it has a distinct focus on Germany, but it already embraced the European dimension:

- the phasing out of ‘zonal boundaries’ and ‘barriers’ with the perspective of ‘maximum possible unification’ in case ‘complete unification cannot be achieved’

- the promise to put an end to ‘needless aggravation of economic distress’ with the help of ‘a common financial policy’ and other ‘central administrative departments’

- the perspective of obtaining ‘the right to manage their own internal affairs as soon as they were able to so in a democratic way’

- but most of all the firm commitment to stay and accompany this long process, as expressed in the opening quote of this post.

In colloquial understanding, the Speech of Hope was interpreted by the locals as ‘we will be punished, but not forever’, ‘we will be given another chance, work hard and improve our lot’, ‘we will be protected from Soviet rule’. Had the material situation not been as utterly distressful as it was in 1946, it could have been called the ‘Speech of Relief’.

Many years later

Three quarters of a century have passed. Everything that seemed a faint glimpse of hope to my parents – my mother was 18 when James Byrne spoke in her hometown – has come true for my generation. The nation-building carried out by the United States with significant help by the United Kingdom and the French Republic is nothing short of a miracle. I know that historians can enumerate many good reasons why it worked out so well in Germany and failed elsewhere. I also realise just how much Germany and Western Europe owe to Stalin’s and Molotov’s ideological unyieldingness and inflexibility. Some consider that it is high time Germany itself shows more of the same commitment and generosity in the different contexts of today. They are not entirely wrong. In a 2015 article, Yanis Varoufakis even referred explicitly to the Speech of Hope as a source of historic responsibility. At the same time, as the negotiation of the EU recovery plan has shown, it would also be wrong to deny German leaders all sense of solidarity for their partners in the Union. While everybody is free to apply their own terms of assessment for Germany’s role in Europe today, it is difficult not to be in awe of (and, as a European citizen, grateful for) what has been achieved by the Allies in post-war Germany. Byrnes closed his speech, which was very straightforward in recalling all the horrors and crimes of the recent past, with a very clear vision: ‘The American people want to help the German people to win their way back to an honourable place among the free and peace-loving nations of the world.’ He did not say ‘boring’. But 75 years later, the boring, dull, risk-averse and often over-cautious nature of German democracy, in its functioning and in its choice of leading human resources, is no doubt one of the greatest vindications of the vision outlined in the Speech of Hope.

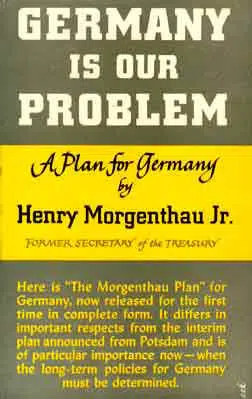

Featured photo: James F. Byrnes am 6. September 1946 bei seiner „Rede der Hoffnung“ im Württembergischen Staatstheater. Foto: Stadtarchiv Stuttgart, F55489