The following question – Is it possible to separate people from their roles? – is a transformation of the one posed by Juliette Clerc in a recent article in the French cultural magazine Télérama: “Is it still possible to separate men from their creations?” (1). Her article does not use the concept of role. Rather, it discusses the relationship between man and work, for example when it mentions “this secular distinction, man versus artwork,” or when it affirms that “the firm boundary between man and artwork, which forms the basis of an aesthetic vision of criticism, takes on water when the view becomes societal.” However, referring to the cases which she is studying (which raise in particular the question of moral and legal responsibility), Juliette Clerc states that “the artist is the man, the man is the artist,” which amounts to implicitly associating the qualification of artist with the role he plays in the forefront of society.

The following question – Is it possible to separate people from their roles? – is a transformation of the one posed by Juliette Clerc in a recent article in the French cultural magazine Télérama: “Is it still possible to separate men from their creations?” (1). Her article does not use the concept of role. Rather, it discusses the relationship between man and work, for example when it mentions “this secular distinction, man versus artwork,” or when it affirms that “the firm boundary between man and artwork, which forms the basis of an aesthetic vision of criticism, takes on water when the view becomes societal.” However, referring to the cases which she is studying (which raise in particular the question of moral and legal responsibility), Juliette Clerc states that “the artist is the man, the man is the artist,” which amounts to implicitly associating the qualification of artist with the role he plays in the forefront of society.

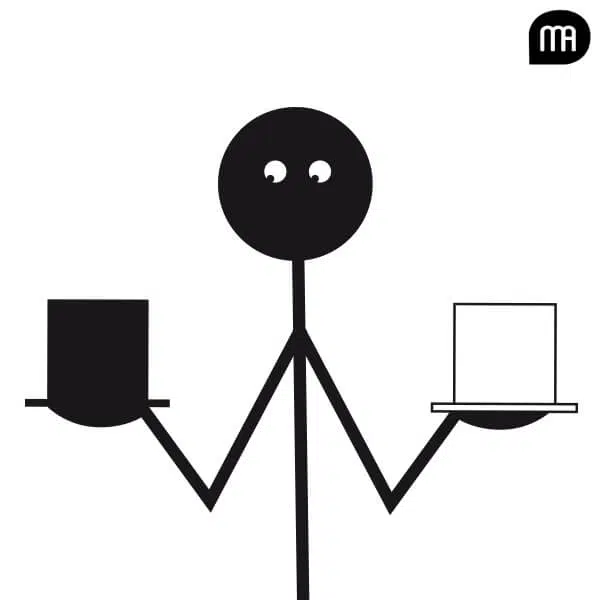

The two sides of the debate

The fact that the concept of role as such is not in the forefront is not surprising. Nor was it in the forefront of the debate on the same theme organised by the New York Times in 2009, in its Room for Debate page (2). Nine personalities had taken a position on the following theme:

“Should society separate the work of artists from the artists themselves, despite evidence of reprehensible or even criminal behavior?”

There was the “secular distinction, man versus artwork.” One of the comments expressed this forcefully:

“Can one really separate the art from the man or woman who creates that art? The answer is yes, definitely. […]

Hideous people can make great art. Wagner is a case in point. He was a magnificent composer, but his personal failings — including a huge streak of anti-Semitism — were reprehensible. His vileness as a man has no bearing on his greatness as a composer. It’s just another subject.”

The opposite perspective was also present. It considered less the position and power of the artist than the relative moral immunity he or she enjoys almost by definition, since he or she has the freedom to transgress social rules:

“The artistic genius acted through transgressing, not obeying conventional principles of art. It was a short step from seeing such artists as free of artistic rules to seeing them as liberated from rules of conduct in general.

[…]

But the defense, legal or otherwise, of ideas, images, and representations of behavior on stage and screen is not a protection of an artist’s ideas or actions outside of artistic contexts.”

Naturally, the abuse of social position and power has also been invoked to denounce the supposed separation between man and artist. It is mentioned in another article in the New York Times, by journalist Amanda Hess, especially in the sentence “men stand accused of using their creative positions to offend,” and in the following excerpt:

“Whenever a creative type (usually a man) is accused of mistreating people (usually women), a call arises to prevent those pesky biographical details from sneaking our assessments of the artist’s work. But the Hollywood players accused of sexual harassment or worse […] have never seemed too interested in separating their art from their misdeeds. We’re learning more every day about how the entertainment industry has been shaped by their abuses of power.”

Two explanations for the apparent absence of the concept of role

The concept of role – that of the artist – is also absent here. Admittedly, the reference to social position, or status, seems to implicitly introduce the idea of role. But this reference is associated with the fact that those in a high social position enjoy great prestige with others. Two explanations can be advanced for the apparent eclipse of the concept of role in current discussions on the separation between the artist and man.

The distinction between role morality and ordinary morality is not relevant

The first, which is well known in the field of applied ethics, concerns morality that is derived from a role. Taking on a role, for example in an organisation, entails specific obligations, such as the obligation of loyalty and obligations related to one’s profession. These moral specificities may go as far as derogations from the principles of ordinary morality – in this respect, the role of the lawyer is undoubtedly the one most often discussed. But, in cases that concern the article of Télérama, such moral derogations are excluded. While the artist’s role may include transgressions, it does not allow the violation of the principles of ordinary morality. As the question of the relationship betwen role morality and ordinary morality is not relevant, the concept of role itself is eclipsed from the debate.

It is not necessary to define the role of the artist

The second explanation for the apparent eclipse of the concept of role is that the definition of the artist’s role seems to have little or no effect on the moral judgment in the cases in question. Perhaps it is due to the plurality of possible definitions of this specific role. But this state of affairs deserves a brief review. The definition proposed by Henri Bergson, according to which

“art, whether it be painting or sculpture, poetry or music, has no other object than to brush aside the utilitarian symbols, the conventional and socially accepted generalities, in short, everything that veils reality from us, in order to bring us face to face with reality itself” (4),

or that of Albert Camus, who gives the artist a political role, even if this role is not a voluntary commitment:

“the artist is willy-nilly impressed into service. ‘Impressed’ seems to me a more accurate term in this connection than ‘committed.’ Instead of signing up, indeed, for voluntary service, the artist does his compulsory service. Every artist today is embarked on the contemporary slave galley” (5),

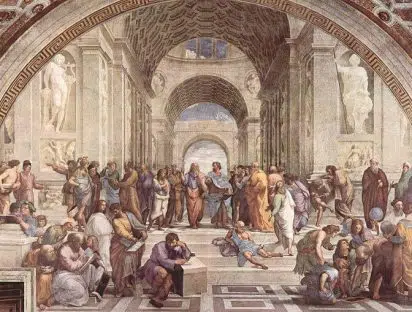

could shed light on the question of whether man and artist can be separated. He who reveals “a deep-seated reality that is veiled from us” (Bergson), or he who, from now on, is no longer isolated from the world but is “in the amphitheater” (Camus), is not only the artist, but also the self which occupies the role of the artist. The true perception of reality or the fact of being caught in the world affect both modes of existence, that of the artist and that of the self. Undoubtedly, this reinforces the statement in Télérama’s article that “the artist is the man, the man is the artist.” But the dual relationship of identity between man and artist has a meaning that goes beyond the sole point of view of moral and legal responsibility. And from this perspective – a philosophical, anthropological, sociological and psychological perspective –, it deserves to be considered. Alain Anquetil (1) « Clap de fin pour l’impunité ? », Télérama, 3645, 20 November 2019. (2) « The Polanski uproar », The New York Times, 29 September 2009. (3) « How the myth of the artistic genius excuses the abuse of women », The New York Times, 10 November 2017. (4) H. Bergson, Le rire. Essai sur la signification du comique, 1900, Paris, PUF, 1978, translated by C. Brereton and F. Rothwell, Laughter: An Essay on the Meaning of the Comic, Project Gutenberg, 2002. (5) A. Camus, Resistance, Rebellion, and Death: Essays, translated by J. O’Brien, New York, Modern Library, 1960. [cite]