Utilitarianism “accepts as the foundation of morals, Utility, or the Greatest Happiness Principle,” according to which “actions are right in proportion as they tend to promote happiness, wrong as they tend to produce the reverse of happiness” (1). This principle seems to be embodied in the aim of effective altruism, which is to do as much good as possible in a rational way, and in the raison d’être of OpenAI, the company that created ChatGPT: “to ensure that artificial general intelligence benefits all of humanity” (2). These apparent affinities deserve a little examination.

Effective altruism has a well-known affinity with utilitarianism.

According to philosopher William Macaskill, who coined the term “effective altruism,” this “way of thinking” reflects an attitude that, in his words, “is about asking ‘How can I make the biggest difference I can?’ and using evidence and careful reasoning to try to find an answer” (3).

Macaskill is careful to distinguish between the two terms in the phrase. “Altruism” refers to “improving lives of others,” which for an effective altruist should not involve sacrificing personal interests. “Effective” refers to “doing the most good with whatever resources you have.”

Macaskill emphasises the idea of maximisation: “Effective altruism is not just about making a difference, or doing some amount of good. It’s about trying to make the most difference you can,” for example by giving the maximum of one’s income (without compromising the quality of one’s life) to organisations that will make the best use of it for the general good.

The moral reasoning of a genuine and effective altruist should aim at producing the best consequences. Utilitarianism is the best known manifestation of this “consequentialism.” Prominent proponents of effective altruism are either committed utilitarians (e.g. Peter Singer) or personalities who have sympathy for consequentialism (e.g. William Macaskill). It should be added that some critics of effective altruism equate it with a version of utilitarianism, but this cannot speak in favour of the affinity in question (4).

Peter Singer notes that although effective altruists are not necessarily utilitarians, they do have some things in common: “In particular, they agree with utilitarians that, other things being equal, we ought to do the most good we can” (5).

However, Benjamin Todd, another advocate of this movement, points out three differences with utilitarianism: first, effective altruism does not require sacrificing one’s self-interest to do the most good for others; second, it rejects the idea that the end can justify the means (but utilitarianism does not necessarily accept this condition); and third, effective altruism claims neither that the good to be achieved is the sum total of the well-being of individuals (which would allow for an unequal distribution of well-being), nor that “well-being is the only thing of value” (6).

Ultimately, according to Todd, what brings effective altruism closer to utilitarianism is reduced to the idea of maximisation.

The same could be said of OpenAI’s mission. The idea of maximisation is explicitly present in the principles that guide its action:

- “We want AGI to empower humanity to maximally flourish in the universe. We don’t expect the future to be an unqualified utopia, but we want to maximize the good and minimize the bad, and for AGI to be an amplifier of humanity.

- We want the benefits of, access to, and governance of AGI to be widely and fairly shared.

- We want to successfully navigate massive risks. In confronting these risks, we acknowledge that what seems right in theory often plays out more strangely than expected in practice. We believe we have to continuously learn and adapt by deploying less powerful versions of the technology in order to minimize ‘one shot to get it right’ scenarios.” (7)

These principles contain concepts that are likely to refer to a moral theory (8):

- human flourishing,

- maximising good and minimising harm,

- fairness (the fair sharing of the benefits of general artificial intelligence),

- safety (managing the “massive risks” of artificial intelligence – “AI safety”),

- and caution, a notion that does not appear explicitly in the previous extract but is the subject of a subsequent paragraph (9).

The reference to ‘human flourishing’ could refer to an attractive conception of morality. According to this conception, of which virtue ethics is a typical example, it is the good that matters (it designates what is valuable), and the right follows from it (it designates what should be done or what is appropriate in a given situation) (10).

But utilitarianism is not an attractive conception of morality, but an imperative one, which is based on the duties and obligations imposed on every agent. Even if it is based on a notion of the good (human fulfilment, which we will specify a little later), it is first and foremost a theory of the right. Charles Larmore offers a suggestive description for our purpose:

“Right action consists in doing whatever will bring about the most good overall, for all those affected by the action, each of them ‘counting for one and only one.’ But this does not mean that the idea of right action is derived from an independent notion of the good. For the good to be maximized is itself specified by appeal to a categorical principle of right: the good is defined by our considering impartially, as it is claimed we ought to do, the total good of all individuals involved, whatever our own interests may be, and thus the duty to pursue it is one binding upon us unconditionally.” (11)

The idea that “right action consists in doing whatever will bring about the most good overall, for all those affected by the action” represents the consequentialist part of utilitarianism (the rightness of the action is assessed by the consequences it produces, given the conditions of equality and impartiality that are specified below), but it also has a prescriptive dimension, a dimension that Monique Canto-Sperber and Ruwen Ogien summarise by stating that “what is primary in utilitarian conceptions is the obligation to produce the greatest happiness for the greatest number” (12).

This obligation is not, however, expressed as such in the rationale for OpenAI, as it is the verb “to want,” not a verb of obligation, that is used in the following statement: “we want to maximize the good and minimize the bad.” But it can legitimately be understood as an obligation: “We ought to maximize the good and minimize the bad.”

The quest to maximise the global good relies on conditions of equality and fairness in the treatment of individuals – in Larmore’s terms: each “counting for one and only one”, “considering impartially, as it is claimed we ought to do, the total good of all individuals involved” (13). These conditions seem to be represented in OpenAI’s Principle 2: “We want the benefits of, access to, and governance of AGI to be widely and fairly shared.”

OpenAI’s raison d’être does not define the good that the company wishes to maximise as Larmore does. It essentially refers to human flourishing, which includes “incredible new capabilities” that general artificial intelligence could develop – cognitive capabilities, ingenuity and creativity (14). It also includes safety and caution to avoid possible abuses in the use of general AI, which could for example lead to abuse of power (15). The important point for our purpose is that this good acts as a criterion of right and wrong. Together with the two criteria discussed above (prescriptivism and consequentialism), it constitutes the third criterion of utilitarianism (16).

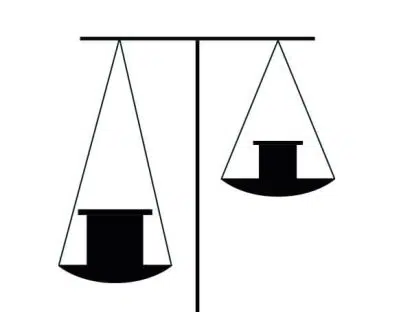

We can conclude our brief exploration here. If we were to place the philosophies of effective altruism and OpenAI in a moral category, we would at first sight choose utilitarianism, mainly because of the importance of maximising the good and the associated conditions of equality and fairness. A second, more ancillary reason may also be advanced: it concerns the moral intuitions that underlie utilitarian reasoning, intuitions that could be “activated” by the philosophies of effective altruism and OpenAI – this is a debatable reason (17), but one that can be said, at the risk of being vague, to have some reality.

References

(1) J. S. Mill, Utilitarianism, 1863, Collected Works of John Stuart Mill, J. M. Robson (ed.), Toronto & Londres, 33 volumes, CW X.

(2) Source: About OpenAI.

(3) W. Macaskill, Doing good better: Effective altruism and a radical new way to make a difference, Guardian Books and Faber & Faber, 2015.

(4) B. Berkey, “The philosophical core of effective altruism,” Journal of Social Philosophy, 52(1), 2021, pp. 93-115. According to Berkey, “a recent survey of self-identified effective altruists found that 56% identified as utilitarians, with another13% identifying as non-utilitarian consequentialists.” Critics of effective altruism who equate it with utilitarianism are cited in B. Todd, “Effective altruism is widely misunderstood, even among its supporters,” 80,000 Hours, 7 August 2020.

(5) P. Singer, The most good you can do. How Effective Altruism is changing ideas about living ethically, Yale University Press, 2015.

(6) B. Todd, op. cit.

(7) Source: About OpenAI.

(8) A moral theory is “an abstract construction that aims to systematise our moral intuitions, the underlying purpose of the exercise [being] to obtain a reflexive framework, consisting of one or more principles applicable to particular actions that allows us to determine whether or not they are morally right” (R. Ogien & C. Tappolet, Les concepts de l’éthique. Faut-il être conséquentialiste ? Hermann Editeurs, 2009).

(9) “Our decisions will require much more caution than society usually applies to new technologies, and more caution than many users would like” (source: About OpenAI).

(10) On the attractive conception of morality (and the imperative conception, discussed soon after), see C. Larmore, The morals of modernity, Cambridge University Press, 1996. On the definitions of the good and the right, see P. Pettit, “Conséquentialisme,” in M. Canto-Sperber (ed.), Dictionnaire d’éthique et de philosophie morale, PUF, 1996.

(11) C. Larmore, op. cit. The excerpt concerns consequentialism, of which utilitarianism is a variant.

(12) M. Canto-Sperber & R. Ogien, op. cit.

(13) C. Larmore, op. cit.

(14) “We can imagine a world in which humanity flourishes to a degree that is probably impossible for any of us to fully visualize yet. We hope to contribute to the world an AGI aligned with such flourishing” (source: About OpenAI).

(15) Source: About OpenAI.

(16) See C. Audard, “Utilitarisme,” in M. Canto-Sperber (ed.), Dictionnaire d’éthique et de philosophie morale, PUF, 1996.

(17) See R. Ogien, L’influence de l’odeur des croissants chauds sur la bonté humaine et autres questions de philosophie morale expérimentale, Editions Grasset & Fasquelle, 2011.

To cite this article: Alain Anquetil, “Are Effective altruism and OpenAI incarnations of utilitarian thinking?” Philosophy & Business Ethics Blog, 18 March 2023.